|

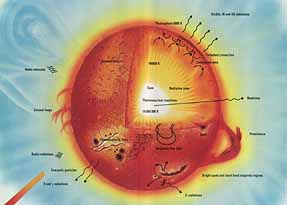

The Sun is the most prominent feature in our solar system. It is the largest object and contains approximately 98% of the

total solar system mass. One hundred and nine Earths would be required to fit across the Sun's disk, and its interior could

hold over 1.3 million Earths. The Sun's outer visible layer is called the photosphere and has a temperature of 6,000°C (11,000°F).

This layer has a mottled appearance due to the turbulent eruptions of energy at the surface.

Solar energy is created deep within the core of the Sun. It is here that the temperature (15,000,000° C; 27,000,000° F)

and pressure (340 billion times Earth's air pressure at sea level) is so intense that nuclear reactions take place. This reaction

causes four protons or hydrogen nuclei to fuse together to form one alpha particle or helium nucleus. The alpha particle is

about .7 percent less massive than the four protons. The difference in mass is expelled as energy and is carried to the surface

of the Sun, through a process known as convection, where it is released as light and heat. Energy generated in the Sun's core takes a million years to reach its surface. Every

second 700 million tons of hydrogen are converted into helium ashes. In the process 5 million tons of pure energy is

released; therefore, as time goes on the Sun is becoming lighter.

The chromosphere is above the photosphere. Solar energy passes through this region on its way out from the center of the

Sun. Faculae and flares arise in the chromosphere. Faculae are bright luminous hydrogen clouds which form above regions where

sunspots are about to form. Flares are bright filaments of hot gas emerging from sunspot regions. Sunspots are dark depressions

on the photosphere with a typical temperature of 4,000°C (7,000°F).

The corona is the outer part of the Sun's atmosphere. It is in this region that prominences appears. Prominences

are immense clouds of glowing gas that erupt from the upper chromosphere. The outer region of the corona stretches far into

space and consists of particles traveling slowly away from the Sun. The corona can only be seen during total solar eclipses.

(See Solar Eclipse Image).

The Sun appears to have been active for 4.6 billion years and has enough fuel to go on for another five billion years or

so. At the end of its life, the Sun will start to fuse helium into heavier elements and begin to swell up, ultimately growing

so large that it will swallow the Earth. After a billion years as a red giant, it will suddenly collapse into a white dwarf -- the final end product of a star like ours. It may take a trillion years to cool off completely.

| Sun Statistics |

| Mass (kg) |

1.989e+30 |

| Mass (Earth = 1) |

332,830 |

| Equatorial radius (km) |

695,000 |

| Equatorial radius (Earth = 1) |

108.97 |

| Mean density (gm/cm^3) |

1.410 |

| Rotational period (days) |

25-36* |

| Escape velocity (km/sec) |

618.02 |

| Luminosity (ergs/sec) |

3.827e33 |

| Magnitude (Vo) |

-26.8 |

| Mean surface temperature |

6,000°C |

| Age (billion years) |

4.5 |

| Principal chemistry

Hydrogen

Helium

Oxygen

Carbon

Nitrogen

Neon

Iron

Silicon

Magnesium

Sulfur

All

others |

92.1%

7.8%

0.061%

0.030%

0.0084%

0.0076%

0.0037%

0.0031%

0.0024%

0.0015%

0.0015% |

* The Sun's period of rotation at the surface varies from approximately 25 days at the equator to 36 days at the poles.

Deep down, below the convective zone, everything appears to rotate with a period of 27 days.

Sun Prominence Sun Prominence

This image was acquired from NASA's Skylab space station on December 19, 1973. It shows one of the most spectacular solar

flares ever recorded, propelled by magnetic forces, lifting off from the Sun. It spans more than 588,000 km (365,000 miles)

of the solar surface. In this photograph, the solar poles are distinguished by a relative absence of supergranulation network,

and a much darker tone than the central portions of the disk. (Courtesy NASA)

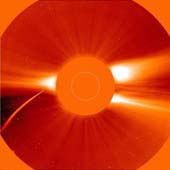

Comet SOHO-6 and Solar Polar Plumes Comet SOHO-6 and Solar Polar Plumes

This image of the solar corona was acquired on 23 December 1996 by the LASCO instrument on the SOHO spacecraft. It shows

the inner streamer belt along the Sun's equator, where the low latitude solar wind originates and is accelerated. Over the

polar regions, one sees the polar plumes all the way out to the edge of the field of view. The field of view of this coronagraph

encompasses 8.4 million kilometers (5.25 million miles) of the inner heliosphere. The frame was selected to show Comet SOHO-6,

one of seven sungrazers discovered so far by LASCO, as its head enters the equatorial solar wind region. It eventually plunged

into the Sun. (Courtesy ESA/NASA)

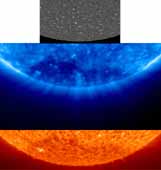

Sources of the Solar Wind? Sources of the Solar Wind?

"Plumes" of outward flowing, hot gas in the Sun's atmosphere may be one source of the solar "wind" of charged particles.

These images, taken March 7, 1996, by the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), show (top) magnetic fields on the sun's

surface near the south solar pole; (middle) an ultraviolet image of the 1 million degree plumes from the same region; and

(bottom) an ultraviolet image of the "quiet" solar atmosphere closer to the surface. (Courtesy ESA/NASA)

The Unquiet Sun The Unquiet Sun

This sequence of images of the the Sun in ultraviolet light was taken by the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO)

spacecraft on February 11, 1996 from its unique vantage point at the "L1" gravity neutral point 1 million miles sunward from

the Earth. An "eruptive prominence" or blob of 60,000°C gas, over 80,000 miles long, was ejected at a speed of at least 15,000

miles per hour. The gaseous blob is shown to the left in each image. These eruptions occur when a significant amount of cool

dense plasma or ionized gas escapes from the normally closed, confining, low-level magnetic fields of the Sun's atmosphere

to streak out into the interplanetary medium, or heliosphere. Eruptions of this sort can produce major disruptions in the

near Earth environment, affecting communications, navigation systems and even power grids. (Courtesy ESA/NASA)

A New Look at the Sun A New Look at the Sun

This image of 1,500,000°C gas in the Sun's thin, outer atmosphere (corona) was taken March 13, 1996 by the Extreme Ultraviolet

Imaging Telescope onboard the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft. Every feature in the image traces magnetic

field structures. Because of the high quality instrument, more of the subtle and detail magnetic features can be seen than

ever before. (Courtesy ESA/NASA)

X-Ray Image X-Ray Image

This is an X-ray image of the Sun obtained on February 21, 1994. The brighter regions are sources of increased X-ray

emissions. (Courtesy Calvin J. Hamilton, and Yohkoh)

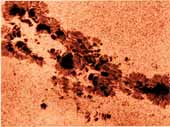

Solar Disk in H-Alpha Solar Disk in H-Alpha

This is an image of the Sun as seen in H-Alpha. H-Alpha is a narrow wavelength of red light that is emitted and absorbed by the element hydrogen. (Courtesy National

Solar Observatory/Sacramento Peak)

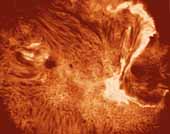

Solar Flare in H-Alpha Solar Flare in H-Alpha

This is an image of a solar flare as seen in H-Alpha. (Courtesy National Solar Observatory/Sacramento Peak)

Solar Magnetic Fields Solar Magnetic Fields

This image was acquired February 26, 1993. The dark regions are locations of positive magnetic polarity and the light

regions are negative magnetic polarity. (Courtesy GSFC NASA)

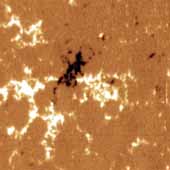

Sun Spots Sun Spots

This image shows the region around a sunspot. Notice the mottled appearance. This granulation is the result of turbulent eruptions of energy at the surface. (Courtesy

National Solar Observatory/Sacramento Peak)

1991 Solar Eclipse 1991 Solar Eclipse

This image shows the total solar eclipse of July 11, 1991 as seen from Baja California. It is a digital mosaic derived

from five individual photographs, each exposed correctly for a different radius in the solar corona. (Courtesy Steve Albers, Dennis DiCicco, and Gary Emerson)

1994 Solar Eclipse 1994 Solar Eclipse

This picture of the 1994 solar eclipse was taken November 3, 1994, as observed by the High Altitude Observatory White

Light Coronal camera from Chile. (Courtesy HAO, NCAR)

|