Venus, the

jewel of the sky, was once know by ancient astronomers as the

morning star and

evening star. Early

astronomers once thought Venus to be two separate bodies. Venus, which is named after the Roman goddess of love and beauty,

is veiled by thick swirling cloud cover.

Astronomers refer to Venus as Earth's sister planet. Both are similar in size, mass, density and volume. Both formed about

the same time and condensed out of the same nebula. However, during the last few years scientists have found that the kinship ends here. Venus is very different from the Earth.

It has no oceans and is surrounded by a heavy atmosphere composed mainly of carbon dioxide with virtually no water vapor.

Its clouds are composed of sulfuric acid droplets. At the surface, the atmospheric pressure is 92 times that of the Earth's at sea-level.

Venus is scorched with a surface temperature of about 482° C (900° F). This high temperature is primarily due to a runaway

greenhouse effect caused by the heavy atmosphere of carbon dioxide. Sunlight passes through the atmosphere to heat the surface of the planet.

Heat is radiated out, but is trapped by the dense atmosphere and not allowed to escape into space. This makes Venus hotter

than Mercury.

A Venusian day is 243 Earth days and is longer than its year of 225 days. Oddly, Venus rotates from east to west. To an

observer on Venus, the Sun would rise in the west and set in the east.

Until just recently, Venus' dense cloud cover has prevented scientists from uncovering the geological nature of the surface.

Developments in radar telescopes and radar imaging systems orbiting the planet have made it possible to see through the cloud

deck to the surface below. Four of the most successful missions in revealing the Venusian surface are NASA's Pioneer Venus

mission (1978), the Soviet Union's Venera 15 and 16 missions (1983-1984), and NASA's Magellan radar mapping mission (1990-1994).

As these spacecraft began mapping the planet a new picture of Venus emerged.

Venus' surface is relatively young geologically speaking. It appears to have been completely resurfaced 300 to 500 million

years ago. Scientists debate how and why this occurred. The Venusian topography consists of vast plains covered by lava flows

and mountain or highland regions deformed by geological activity. Maxwell Montes in Ishtar Terra is the highest peak on Venus.

The Aphrodite Terra highlands extend almost half way around the equator. Magellan images of highland regions above 2.5 kilometers

(1.5 miles) are unusually bright, characteristic of moist soil. However, liquid water does not exist on the surface and cannot

account for the bright highlands. One theory suggests that the bright material might be composed of metallic compounds. Studies

have shown the material might be iron pyrite (also know as "fools gold"). It is unstable on the plains but would be stable

in the highlands. The material could also be some type of exotic material which would give the same results but at lower concentrations.

Venus is scarred by numerous impact craters distrubuted randomly over its surface. Small craters less that 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) are almost non-existent due to the

heavy Venusian atmosphere. The exception occurs when large meteorites shatter just before impact, creating crater clusters. Volcanoes and volcanic features are even more numerous. At least 85% of the Venusian surface is covered with volcanic rock.

Hugh lava flows, extending for hundreds of kilometers, have flooded the lowlands creating vast plains. More than 100,000 small

shield volcanoes dot the surface along with hundreds of large volcanos. Flows from volcanos have produced long sinuous channels

extending for hundreds of kilometers, with one extending nearly 7,000 kilometers (4,300 miles).

Giant calderas more than 100 kilometers (62 miles) in diameter are found on Venus. Terrestrial calderas are usually only several kilometers

in diameter. Several features unique to Venus include coronae and arachnoids. Coronae are large circular to oval features,

encircled with cliffs and are hundreds of kilometers across. They are thought to be the surface expression of mantle upwelling.

Archnoids are circular to elongated features similar to coronae. They may have been caused by molten rock seeping into surface

fractures and producing systems of radiating dikes and fractures.

| Venus Statistics |

| Mass (kg) |

4.869e+24 |

| Mass (Earth = 1) |

.81476 |

| Equatorial radius (km) |

6,051.8 |

| Equatorial radius (Earth = 1) |

.94886 |

| Mean density (gm/cm^3) |

5.25 |

| Mean distance from the Sun (km) |

108,200,000 |

| Mean distance from the Sun (Earth = 1) |

0.7233 |

| Rotational period (days) |

-243.0187 |

| Orbital period (days) |

224.701 |

| Mean orbital velocity (km/sec) |

35.02 |

| Orbital eccentricity |

0.0068 |

| Tilt of axis (degrees) |

177.36 |

| Orbital inclination (degrees) |

3.394 |

| Equatorial surface gravity (m/sec^2) |

8.87 |

| Equatorial escape velocity (km/sec) |

10.36 |

| Visual geometric albedo |

0.65 |

| Magnitude (Vo) |

-4.4 |

| Mean surface temperature |

482°C |

| Atmospheric pressure (bars) |

92 |

Atmospheric composition

Carbon dioxide

Nitrogen

Trace amounts of: Sulfur dioxide, water vapor,

carbon monoxide, argon, helium, neon,

hydrogen

chloride, and hydrogen fluoride. |

96%

3+% |

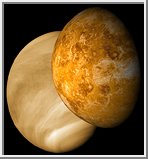

Venus with Visible and Radar Illumination

Venus with Visible and Radar Illumination

This picture shows two different perspectives of Venus. On the left is a mosaic of images acquired by the Mariner 10

spacecraft on February 5, 1974. The image shows the thick cloud coverage that prevents optical observation of the planet's

surface. The surface of Venus remained hidden until 1978 when the Pioneer Venus 1 spacecraft arrived and went into orbit about

the planet on December 4th. The spacecraft used radar to map planet's surface, revealing a new Venus. Later in August of 1990

the Magellan spacecraft arrived at Venus and began its extensive planetary mapping mission. This mission produced radar images

up to 300 meters per pixel in resolution. The right image show a rendering of Venus from the Pioneer Venus and Magellan radar

images. (Copyright Calvin J. Hamilton)

The Interior of Venus

The Interior of Venus

This picture shows a cutaway view of the possible internal structure of Venus. The image was created from Mariner 10

images used for the outer atmospheric layer. The surface was taken from Magellan radar images. The interior characteristics

of Venus are inferred from gravity field and magnetic field measurements by Magellan and prior spacecraft. The crust is shown

as adark red, the mantle as a lighter orange-red, and the core yellow. More ... (Copyright Calvin J. Hamilton)

Mariner 10 Image of Venus

Mariner 10 Image of Venus

This beautiful image of Venus is a mosaic of three images acquired by the Mariner 10 spacecraft on February 5, 1974. It shows the thick cloud coverage that prevents optical observation of the surface of Venus.

Only through radar mapping is the surface revealed. (Copyright Calvin J. Hamilton)

Galileo Image of Venus

Galileo Image of Venus

On February 10, 1990 the Galileo spacecraft acquired this image of Venus. Only thick cloud cover can be seen. (Copyright

Calvin J. Hamilton)

Hubble Image of Venus

Hubble Image of Venus

This is a Hubble Space Telescope ultraviolet-light image of the planet Venus, taken on January 24, 1995, when Venus was

at a distance of 113.6 million kilometers from Earth. At ultraviolet wavelengths cloud patterns become distinctive. In particular,

a horizontal "Y" shaped cloud feature is visible near the equator. The polar regions are bright, possibly showing a haze of

small particles overlying the main clouds. The dark regions show the location of enhanced sulfur dioxide near the cloud tops.

From previous missions, astronomers know that such features travel east to west along with the Venus' prevailing winds, to

make a complete circuit around the planet in four days. (Credit: L. Esposito, University of Colorado, Boulder, and NASA)

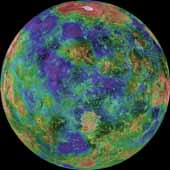

Hemispheric View of Venus

Hemispheric View of Venus

This hemispheric view of Venus, as revealed by more than a decade of radar investigations culminating in the 1990-1994

Magellan mission, is centered at 0 degrees east longitude. The effective resolution of this image is about 3 kilometers. It

was processed to improve contrast and to emphasize small features, and was color-coded to represent elevation. (Courtesy

NASA/USGS)

Additional Hemispheric Views of Venus

Venusian Map

Venusian Map This image is a Mercator projection of Venusian topography. Many of the different regions have been labeled. The map

extends from -66.5 to 66.5 degrees in latitude and starts at 240 degrees longitude.

(Copyright Calvin J. Hamilton)

Venusian Topography Map

Venusian Topography Map This is another Mercator projection of Venusian topography. The map extends from -66.5 to 66.5 degrees in latitude and

starts at 240 degrees longitude. A

Black & White version of this image is also available.

(Courtesy A.Tayfun Oner)  Gula Mons and Crater Cunitz

Gula Mons and Crater Cunitz A portion of Western Eistla Regio is displayed in this three dimensional perspective view of the surface of Venus. The

viewpoint is located 1,310 kilometers (812 miles) southwest of Gula Mons at an elevation of 0.78 kilometers (0.48 mile). The

view is to the northeast with Gula Mons appearing on the horizon. Gula Mons, a 3 kilometer (1.86 mile) high volcano, is located

at approximately 22 degrees north latitude, 359 degrees east longitude. The impact crater Cunitz, named for the astronomer

and mathematician Maria Cunitz, is visible in the center of the image. The crater is 48.5 kilometers (30 miles) in diameter

and is 215 kilometers (133 miles) from the viewer's position.

(Courtesy NASA/JPL)  Eistla Regio - Rift Valley

Eistla Regio - Rift Valley A portion of Western Eistla Regio is displayed in this three dimensional perspective view of the surface of Venus. The

viewpoint is located 725 kilometers (450 miles) southeast of Gula Mons. A

rift valley, shown in the foreground, extends to the base of Gula Mons, a 3 kilometer (1.86 miles) high volcano. This view is facing

the northwest with Gula Mons appearing at the right on the horizon. Sif Mons, a volcano with a diameter of 300 kilometers

(180 miles) and a height of 2 kilometers (1.2 miles), appears to the left of Gula Mons in the background.

(Courtesy NASA/JPL)

Eistla Regio

Eistla Regio A portion of Western Eistla Regio is displayed in this three dimensional perspective view of the surface of Venus. The

viewpoint is located 1,100 kilometers (682 miles) northeast of Gula Mons at an elevation of 7.5 kilometers (4.6 miles). Lava

flows extend for hundreds of kilometers across the fractured plains shown in the foreground, to the base of Gula Mons. This

view faces the southwest with Gula Mons appearing at the left just below the horizon. Sif Mons appears to the right of Gula

Mons. The distance between Sif Mons and Gula Mons is approximately 730 kilometers (453 miles).

(Courtesy NASA/JPL)

Lakshmi Planum

Lakshmi Planum The southern scarp and basin province of western Ishtar Terra are portrayed in this three dimensional perspective view.

Western Ishtar Terra is about the size of Australia and is a major focus of

Magellan investigations. The highland terrain is centered on a 2.5 km to 4 km high (1.5 mi to 2.5 mi high) plateau called Lakshmi

Planum which can be seen in the distance at the right. Here the surface of the plateau drops precipitously into the bounding lowlands,

with steep slopes that exceed 5% over 50 km (30 mi).

(Courtesy NASA/JPL)  Three-Dimensional Perspective View of Alpha Regio

Three-Dimensional Perspective View of Alpha Regio A portion of Alpha Regio is displayed in this three-dimensional perspective view of the surface of Venus. Alpha Regio,

a topographic upland approximately 1300 kilometers across, is centered on 25 degrees south latitude, 4 degrees east longitude.

In 1963, Alpha Regio was the first feature on Venus to be identified from earth-based radar. The radar-bright area of Alpha

Regio is characterized by multiple sets of intersecting trends of structural features such as ridges, troughs, and flat-floored

fault valleys that, together, form a polygonal outline. Directly south of the complex ridged terrain is a large ovoid-shaped

feature named Eve. The radar-bright spot located centrally within Eve marks the location of the prime meridian of Venus.

(Courtesy

NASA/JPL)  Arachnoids

Arachnoids Arachnoids are one of the more remarkable features found on Venus. They are seen on radar-dark plains in this Magellan

image mosaic of the Fortuna region. As the name suggests, arachnoids are circular to ovoid features with concentric rings

and a complex network of fractures extending outward. The arachnoids range in size from approximately 50 kilometers (29.9

miles) to 230 kilometers (137.7 miles) in diameter. Arachnoids are similar in form but generally smaller than coronae (circular

volcanic structures surrounded by a set of ridges and grooves as well as radial lines). One theory concerning their origin

is that they are a precursor to coronae formation. The radar-bright lines extending for many kilometers might have resulted

from an upwelling of magma from the interior of the planet which pushed up the surface to form "cracks." Radar-bright lava

flows are present in the 1st and 3rd image, also indicative of volcanic activity in this area. Some of the fractures cut across

these flows, indicating that the flows occurred before the fractures appeared. Such relations between different structures

provide good evidence for relative age dating of events.

(Courtesy NASA/JPL)  Parallel Lines

Parallel Lines Two groups of parallel features that intersect almost at right angles are visible. The regularity of this terrain caused

scientists to nickname it

graph paper terrain. The fainter lineations are spaced at intervals of about 1 kilometer

(.6 miles) and extend beyond the boundaries of the image. The brighter, more dominant lineations are less regular and often

appear to begin and end where they intersect the fainter lineations. It is not yet clear whether the two sets of lineations

represent faults or fractures, but in areas outside the image, the bright lineations are associated with pit craters and other

volcanic features.

(Courtesy Calvin J. Hamilton)  Surface Photographs from Venera 9 and 10

Surface Photographs from Venera 9 and 10 The Soviet Venera 9 and 10 spacecraft were launched on 8 and 14 June 1975, respectively, to do the unprecedented: place

landers on the surface of Venus and return images. The Venera 9 Lander (top) touched down on the surface of Venus on October

22, 1975 at 5:13 UT, about 32° S, 291° E with the sun near zenith. It operated for 53 minutes, allowing return of a single

image. Venera 9 landed on a slope inclined by about 30 degrees to the horizontal. The white object at the bottom of the image

is part of the lander. The distortion is caused by the Venera imaging system. Angular and partly weathered rocks, about 30

to 40 cm across, dominate the landscape, many partly buried in soil. The horizon is visible in the upper left and right corners.

The Venera 10 Lander (bottom) touched down on the surface of Venus on October 25, 1975 at 5:17 UT, about 16° N, 291° E.

The Lander was inclined about 8 degrees. It returned this image during the 65 minutes of operation on the surface. The sun

was near zenith during this time, and the lighting was similar to that on Earth on an overcast summer day. The objects at

the bottom of the image are parts of the spacecraft. The image shows flat slabs of rock, partly covered by fine-grained material,

not unlike a volcanic area on Earth. The large slab in the foreground extends over 2 meters across.

Color Surface Photographs from Venera 13

Color Surface Photographs from Venera 13

On March 1, 1982 the Venera 13 lander touched down on the Venusian surface at 7.5° S, 303° E, east of Phoebe Regio. It

was the first Venera mission to include a color TV camera. Venera 13 survived on the surface for 2 hours, 7 minutes, long

enough to obtain 14 images. This color panorama was produced using dark blue, green and red filters and has a resolution of

4 to 5 min. Part of the spacecraft is seen at the bottom of the image. Flat rock slabs and soil are visible. The true color

is difficult to judge because the Venerian atmosphere filters out blue light. The surface composition is similar to terrestrial

basalt. On the ground in the foreground is a camera lens cover. This image is the left half of the Venera 13 photo.